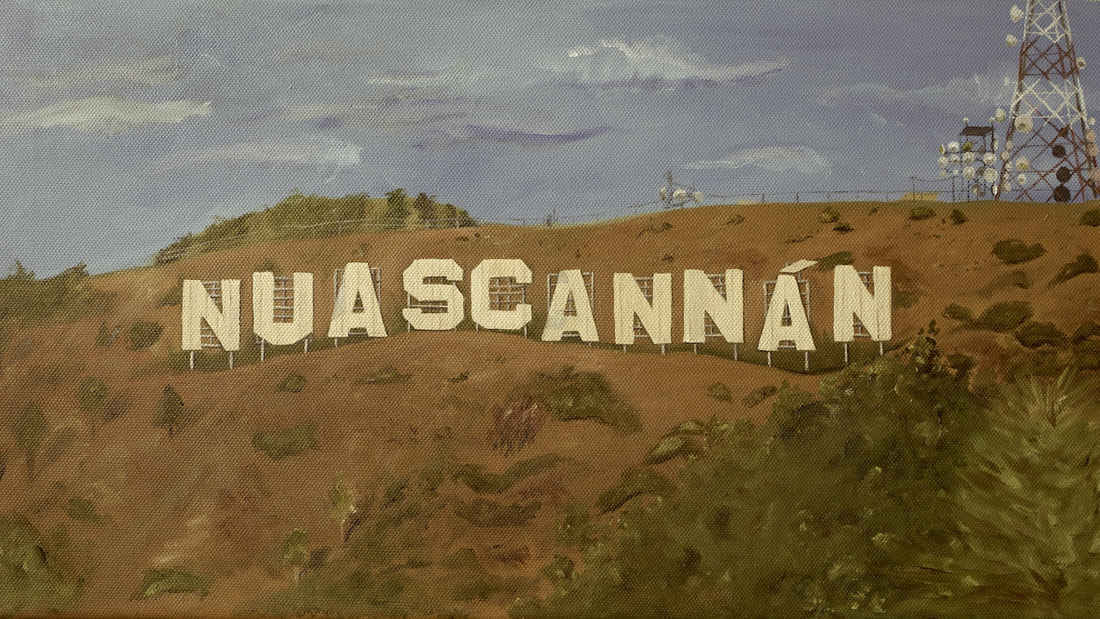

In my native Irish tongue, I fuse the terms 'new' and 'cinema' into the word Nuascannán. Yet this movement is not exclusive to any one nationality - it’s a global uprising. One indebted to clans like Italian Neorealism, the French New Wave and Danish Dogme. For in their own different ways, they laboratory-tested an approach to filmmaking which is crystallising on the internet in our time.

Neorealism was borne of the Italian mid-forties and illuminated a changing mentality in the post-war working class through movies shot on location with non-professional actors. The French New Wave were a group of filmmakers in the late fifties and sixties who despised grand literary period pieces of the day and made experimental films about social-cum-political issues, using portable equipment and sometimes bordering on documentary in terms of style. Perhaps most recently - and didactically - the Dogme manifesto was heralded in the mid-nineties by a few Danish directors who actually went to the extreme of enumerating rules about filmmaking with the hope of grounding balloon-budget cinema in the traditional values of story, acting and theme.

Every time a breath of fresh air occurred, a kind of backlash followed. This was not least because even the cheapest filmmaking remained expensive - until very late in the last century one still had to buy/process/print film, rent a movie camera, procure lights and generally source vehicles and crew. However, in the early years of this one a deep tectonic shift in the landscape of cinema truly began to occur - a shift that might have commenced a few years beforehand in the form of the latter ‘Dogme’ movement but didn’t quite manage to do so, as that category was corralled on primitive standard definition videotape. When the shift truly got underway a few years later it started to fundamentally alter not merely the fledgling filmmaker’s approach to shooting but also cutting, sound mixing and perhaps most significantly distribution. I’m talking, of course, about the wholesale evolution from celluloid to digital and a spectacle that in some respects everyone has witnessed with perfect lucidity - like roughly a hundred years earlier when people observed The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station.

On a deeper level, however, it feels like some have not grasped the ramifications of what is happening.

Every time a breath of fresh air occurred, a kind of backlash followed. This was not least because even the cheapest filmmaking remained expensive - until very late in the last century one still had to buy/process/print film, rent a movie camera, procure lights and generally source vehicles and crew. However, in the early years of this one a deep tectonic shift in the landscape of cinema truly began to occur - a shift that might have commenced a few years beforehand in the form of the latter ‘Dogme’ movement but didn’t quite manage to do so, as that category was corralled on primitive standard definition videotape. When the shift truly got underway a few years later it started to fundamentally alter not merely the fledgling filmmaker’s approach to shooting but also cutting, sound mixing and perhaps most significantly distribution. I’m talking, of course, about the wholesale evolution from celluloid to digital and a spectacle that in some respects everyone has witnessed with perfect lucidity - like roughly a hundred years earlier when people observed The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station.

On a deeper level, however, it feels like some have not grasped the ramifications of what is happening.

I directed my first feature in the mid-nineties on Super 16mm film with heavy lights, generators and a fleet of vehicles carrying

equipment, cast and crew. When the film went on general release around my country, it was blown up to 35mm reels like many an indie movie before it such as The Evil Dead, Leaving Las Vegas or The Snapper. Yet having recently finished shooting my seventh feature, I can also state for the record that all my movies nowadays are shot and released 100% digitally. They can play on big screens which are predominantly digital screens anyway, yet be sent to any digital screen whatsoever and are created by switching on equipment that is equally digital to begin with. Digital and increasingly small. Indeed - when cine cameras get this small it also becomes possible for us to shrink dollies, cranes and even the aircraft that allow them rise above the grounded human perspective and contribute to a story feeling ‘cinematic’.

A movie production used to look like an invading army, but now more closely resembles Andy Warhol taking his famous Polaroids at cocktail parties. How many cinemagoers know that when Natalie Portman accepted her Best Actress Oscar for Black Swan, she was receiving it for a film partly shot on a DSLR? When filmmakers become this inconspicuous, they no longer need to engage hundreds of extras or build entire sets. The real world can sometimes be used instead. This significantly changes who filmmakers are and what filmmaking is - even while safety regulations and the need for permits remain completely unchanged. An interesting case in point is Escape From Tomorrow, which told the story of an unemployed man’s surreal journey during a family vacation at the Walt Disney World Resort and was championed by Roger Ebert.

Mainstream cinema has certainly been suffering an identity crisis of late and had to ask itself difficult questions. Has everything been done? Will the future merely be truckloads of remakes or reboots or revisionism? Is there a stylistic difference, anymore, between the small screen and big screen? Not to mention the scariest question of all - are people still willing to fork out money for movies when they are not physically sitting in a public cinema?

Crucially, this century’s technology doesn’t merely encourage us filmmakers to snaffle our movies in the creative sense, but also tempts viewers to steal them in a literal sense. DVD has declined a lot faster than VOD has grown - that’s legal video streaming to the uninitiated. Does this mean people are watching less movies? On the contrary, it means that many people who watch films online don’t grace the VOD party at all, but head straight for the Bittorrent one. In other words, share movies amongst themselves without paying a cent to the filmmaker. In Sweden, the crowd who run sharing site ‘The Pirate Bay’ have successfully registered the act of sharing as a religion and fight the law at every turn. There is a terrible, creeping feeling within the world of movies that people just don’t pay to watch our work anymore. Which is precisely why cineplexes now seem to be orientated around young families - and why investment for films that don’t fall into that category is becoming even more difficult than it previously was. Ultimately, who can blame cinema audiences and investors for waning when movies can be made and shared with such technical ease? What if those Scandinavian anarchists are right and it’s just not about money!

A backlash is gearing up, as I mentioned it did in the case of those previous waves, but this time it completely lacks force. We can’t stop the revolution. From the perspective of many old school producers, the last ten years have felt like their declining ones and increasingly the best case scenario for the future seems to be entities like Netflix which succeed in squeezing a relatively small - and utterly flat - subscription fee from audiences. The price we used to pay for a couple of new releases in the video store now buys an entire month of movies without our having to leave the couch. These kinds of flat-fee streaming services and traditional cable movie channels will soon become completely indistinguishable from one another and simply be competing for who can offer the lowest subscription fee. HBO and Netflix have been generating very similar figures in terms of subscription revenue - both easing towards $5 billion annually at the time this blog post is being published - and that’s why a lot of the movie world has appeared to bolt desperately under their tents. Recently, even Amazon have gotten in on the act and started producing their own drama.

Many believe this is fast becoming the only game in town. Digital companies that can still theoretically get millions of dollars out of people every month, spending millions on filmmaking. Heaven knows, one can’t raise the necessary finance by distributing ‘feature presentations’ through cinemas or upon discs anymore and so perhaps these mammoth new online studios are the twenty first century update? Yet while different on the surface, such entities aren't truly different underneath, just a diminished version of what once was: a room of executives still believe they control what goes into production and what does not / what screens and what does not. That is a falsehood, the cultural recognition of which will make a deeper difference. The truth is that filmmakers require no such approval anymore, can make the movies they want and distribute them on the internet just like any other title. Indeed, movies not produced by those mainstream companies may have a distinct advantage because while audiences seem increasingly tired of remunerating big old productions, there is no reason to assume their weariness extends to Nuascannán. In fact, there is ample evidence that a completely new relationship between filmmakers and audiences is burgeoning.

If the media wants to support moving pictures in the 21st century, it needs to report more from this new dimension.

Follow x.com/nuascannan and use #nuascannan hashtag for indie movies made the Nuascannán way!

equipment, cast and crew. When the film went on general release around my country, it was blown up to 35mm reels like many an indie movie before it such as The Evil Dead, Leaving Las Vegas or The Snapper. Yet having recently finished shooting my seventh feature, I can also state for the record that all my movies nowadays are shot and released 100% digitally. They can play on big screens which are predominantly digital screens anyway, yet be sent to any digital screen whatsoever and are created by switching on equipment that is equally digital to begin with. Digital and increasingly small. Indeed - when cine cameras get this small it also becomes possible for us to shrink dollies, cranes and even the aircraft that allow them rise above the grounded human perspective and contribute to a story feeling ‘cinematic’.

A movie production used to look like an invading army, but now more closely resembles Andy Warhol taking his famous Polaroids at cocktail parties. How many cinemagoers know that when Natalie Portman accepted her Best Actress Oscar for Black Swan, she was receiving it for a film partly shot on a DSLR? When filmmakers become this inconspicuous, they no longer need to engage hundreds of extras or build entire sets. The real world can sometimes be used instead. This significantly changes who filmmakers are and what filmmaking is - even while safety regulations and the need for permits remain completely unchanged. An interesting case in point is Escape From Tomorrow, which told the story of an unemployed man’s surreal journey during a family vacation at the Walt Disney World Resort and was championed by Roger Ebert.

Mainstream cinema has certainly been suffering an identity crisis of late and had to ask itself difficult questions. Has everything been done? Will the future merely be truckloads of remakes or reboots or revisionism? Is there a stylistic difference, anymore, between the small screen and big screen? Not to mention the scariest question of all - are people still willing to fork out money for movies when they are not physically sitting in a public cinema?

Crucially, this century’s technology doesn’t merely encourage us filmmakers to snaffle our movies in the creative sense, but also tempts viewers to steal them in a literal sense. DVD has declined a lot faster than VOD has grown - that’s legal video streaming to the uninitiated. Does this mean people are watching less movies? On the contrary, it means that many people who watch films online don’t grace the VOD party at all, but head straight for the Bittorrent one. In other words, share movies amongst themselves without paying a cent to the filmmaker. In Sweden, the crowd who run sharing site ‘The Pirate Bay’ have successfully registered the act of sharing as a religion and fight the law at every turn. There is a terrible, creeping feeling within the world of movies that people just don’t pay to watch our work anymore. Which is precisely why cineplexes now seem to be orientated around young families - and why investment for films that don’t fall into that category is becoming even more difficult than it previously was. Ultimately, who can blame cinema audiences and investors for waning when movies can be made and shared with such technical ease? What if those Scandinavian anarchists are right and it’s just not about money!

A backlash is gearing up, as I mentioned it did in the case of those previous waves, but this time it completely lacks force. We can’t stop the revolution. From the perspective of many old school producers, the last ten years have felt like their declining ones and increasingly the best case scenario for the future seems to be entities like Netflix which succeed in squeezing a relatively small - and utterly flat - subscription fee from audiences. The price we used to pay for a couple of new releases in the video store now buys an entire month of movies without our having to leave the couch. These kinds of flat-fee streaming services and traditional cable movie channels will soon become completely indistinguishable from one another and simply be competing for who can offer the lowest subscription fee. HBO and Netflix have been generating very similar figures in terms of subscription revenue - both easing towards $5 billion annually at the time this blog post is being published - and that’s why a lot of the movie world has appeared to bolt desperately under their tents. Recently, even Amazon have gotten in on the act and started producing their own drama.

Many believe this is fast becoming the only game in town. Digital companies that can still theoretically get millions of dollars out of people every month, spending millions on filmmaking. Heaven knows, one can’t raise the necessary finance by distributing ‘feature presentations’ through cinemas or upon discs anymore and so perhaps these mammoth new online studios are the twenty first century update? Yet while different on the surface, such entities aren't truly different underneath, just a diminished version of what once was: a room of executives still believe they control what goes into production and what does not / what screens and what does not. That is a falsehood, the cultural recognition of which will make a deeper difference. The truth is that filmmakers require no such approval anymore, can make the movies they want and distribute them on the internet just like any other title. Indeed, movies not produced by those mainstream companies may have a distinct advantage because while audiences seem increasingly tired of remunerating big old productions, there is no reason to assume their weariness extends to Nuascannán. In fact, there is ample evidence that a completely new relationship between filmmakers and audiences is burgeoning.

If the media wants to support moving pictures in the 21st century, it needs to report more from this new dimension.

Follow x.com/nuascannan and use #nuascannan hashtag for indie movies made the Nuascannán way!